by Claudia Viggiani

translated by Steve Barley

There are works of art which are more fascinating than others not just because they were made by illustrious artists, but because of the awe that they inspire and for the mystery which, often, surrounds them. For example, I adore the Cherubini that Gian Lorenzo Bernini created for the sculpture which portrays the death of Ludovica Albertoni.

In the church of San Francesco a Ripa at the end of the nave on the left is the chapel which Marquis Baldassarre Paluzzi Albertoni bought in 1622 to dedicate to his ancestor Ludovica Albertoni. Ludovica had entered the Third Order of St. Francis and on her death in 1533 at the age of 60 she was immediately venerated as a saint. When, in 1671, Ludovica was officially beatified with the title of “Blessed”, Angelo Altieri Albertoni, nephew of Pope Clement X, commissioned Giacomo Mola and Gian Lorenzo Bernini to refurbish and embellish the chapel just as it is today. The work depicting Ludovica’s death, which was sculpted in Carrara marble by a Bernini of advanced age but with the expertise of a life-time, was completed by 1674 and is as legendary as its terracotta sketch-model in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Less well-known though is the story behind Bernini’s work in transforming Mola’s modest chapel into an exquisite stage where he could set the scene for The Blessed Ludovica’s mystical union with God. Bernini tore down the rear wall and enlarged the chapel – just enough to be able to erect a catafalque for the wooden bed on which Ludovica’s body was laid.

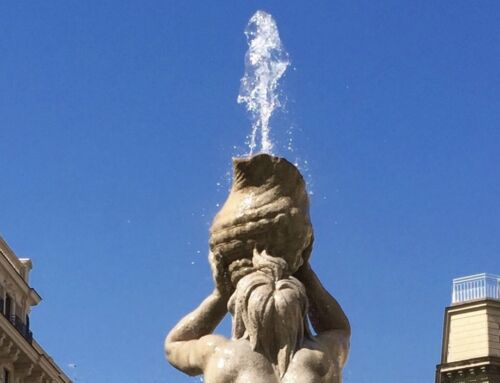

In the walls of this newly-created, arched recess – an arcosolium of ancient memories – Bernini opened windows which are hidden from public view, but which are essential for a seemingly natural illumination of the group. The scene is framed, in a blaze of gold ornament, by ten extraordinary cherubs’ heads in plaster on either side of the altarpiece which depicts The Virgin and Child with St. Anne by Giovanni Battista Gaulli, known as Baciccia. The walling-up of the window on the right, today, limits the enchanting effect that the original illumination of Bernini’s moving composition must have created in its daily and eternal cycle from dawn to dusk.

At the gate to the chapel I ask permission to go inside to get a closer look at the composition and in particular, at the cherubs. With every step forward I take, I feel happier and a vague fear invades me at the thought that the sexton will tell me that my time is up.

Luckily, the minutes pass – several, long minutes. Time stands still both for me and for the sculpture which remains immobile, unchanged, just as it was when Bernini stood back to admire his finished work. But all at once something new happens. A glow of light enters from the window on the left and, as if it were a gust of wind, moves the hair and wings of the precious cherubs who smile while they continue singing.

There is no poetry so great as a dream come true. Bernini puts his creations, his visions, his emotions onto the stage: his idea and his sharing of the passage to an afterlife. Bernini has sculpted the “flight” of his cherubs and their feelings. Together with them I am both witness and protagonist in something which isn’t really happening, but which belongs to the imagination of a great artist, a technical genius, a master of surprise. We, all of us, share the journey of a woman in her mystic agony, in the anguish of her soul, at the climactic moment of her death.

And here I am with Ludovica and with these angels, each with their two unfolded wings.

I move closer. As close as I can. I try to understand how these heads are fixed and held on to the walls.

She becomes agitated, she writhes; perhaps she is afraid. She moves her hands to her midriff, to her heart. She opens her mouth and breathes her last breath while the cherubs watch over her, waiting for the moment when they will take flight together.

I look at the angels’ faces in the half-light and I smile: who knows how many young apprentices worked here with the elderly Bernini, already approaching his eighties?

I lower my gaze and see the alabaster drapes which were added in the Settecento to substitute Bernini’s wooden bedstead.

I leave the chapel, but turn around to look one last time. Without those cherubs the composition just would not be the same.

It is with details, I am sure, that everything is made more beautiful.